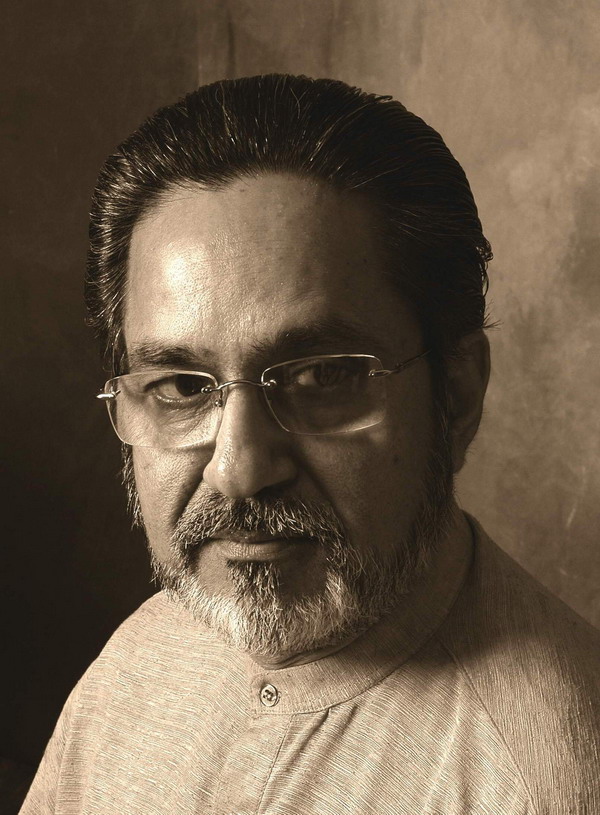

Danish Azar Zuby (15th October 1950 – 4th September 2023), known as DAZ by most of his friends and colleagues, was a Pakistani designer, considered to be one of the important figures in the development of the Interior Design discipline in the country. However, he is also known for being a multidisciplinary design professional who worked in Interior Design, Architecture, Urban design. He was also an activist, a gifted artist and educationist.

Early Life

Danish’s childhood was overshadowed by the trauma of a broken home, with neglect, uncertainty and grief. He was born in Lahore on the 15th of October 1950, to Aziza Khanum and Ozzir Zuby (Inayatullah). His father was a celebrated pioneering sculptor and artist of Pakistan, and had worked with Henry Moore in the 1950s in Italy. The marriage was turbulent from the start and ended in divorce when Danish was only four years old. Ozzir Zuby left his wife and Danish in Lahore and traveled to Karachi with his elder son, Zulfikar Aazeen, to start a new life. Danish’s mother remarried, leaving him to live at a run down place with ailing grandparents. Having been neglected at home he found himself on Beadon Road, as a street child. He was later sent to Karachi at the behest of his mother, but didn’t rejoin his father, who had also remarried. Rather, both he and his brother lived with a paternal aunt who was brought from Lahore by his father to take care of them in a separate house in Soldier Bazar. This was also a very unhappy arrangement as she was very strict and resented having to take care of the two boys, while the father was busy with his new family.

Early Career and Education

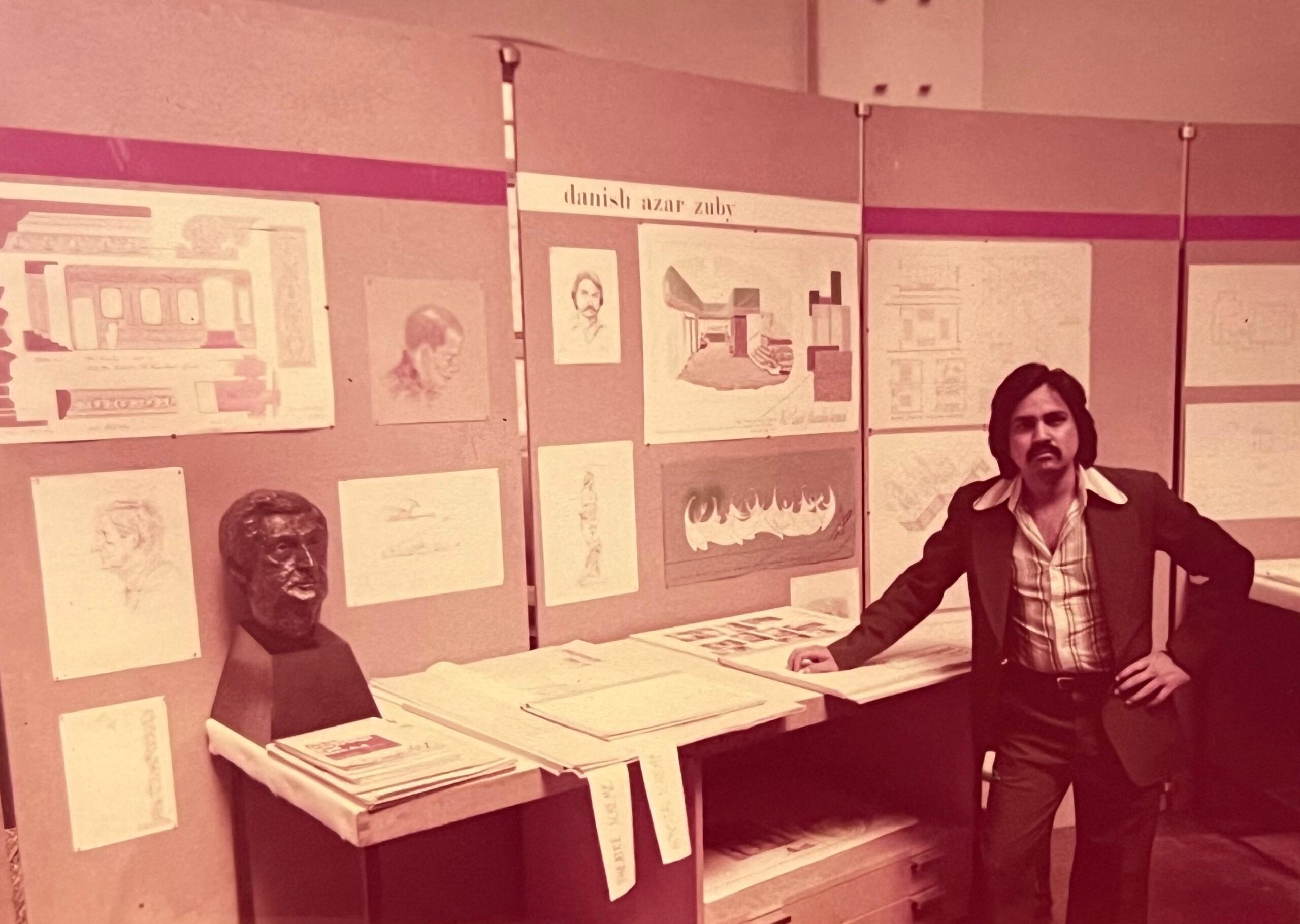

By 1970 Danish had rejoined his father in Karachi and spent time at the Zuby School of Decor, a prized institution of that era where Ozzir Zuby taught multiple Diploma level courses in Art, Sculpture, and Interior Decor. He soon found he was not welcome and was pushed to find his own path by his father. Danish found a job at a local furniture shop, “The Aristocrat” run by entrepreneurs, Maqbool and Noor Hasan. Here he developed his skills of furniture design, technical drawing, manufacturing and salesmanship. This path of work quickly led him to an opportunity to design a boutique in Bahrain. With its immediate success, he decided to start a firm, “Worldecor” in partnership with a local, offering interior decor and manufacturing services. He continued to work and enjoyed the growth of the company until deciding to pursue formal education in design, for which he decided to go to London.

He enrolled himself at the Polytechnic of North London, in the Interior Design Department, in 1976 and stayed there until 1980. During this time, he remained a star student, traveling throughout the United Kingdom and Europe at large. This exposure was a highly transformative experience for him, grounding him in the design traditions from the West, while also opening him up to a multicultural environment of the UK in the late 70s.

In order to meet his expenses he took a job at the Palace Theatre which was playing the celebrated Jesus Christ Superstar show. He was quite enamoured by the experience of working in the theatre and completed his design thesis on it as well. Upon graduation he worked briefly at John Micheal Associates and was also admitted to the British Institute of Interior Designers in 1980. It was also

during this time that he fell in love with a girl from Nebraska, US. The relationship did not last as she returned to the US and he returned to Pakistan in 1980.

Later Career and Recognition

Having returned to Pakistan, Danish found himself at School of Decor again, with his father. With the wealth of knowledge and experience, he presented the idea of making a design firm, “Zuby Design Consultants” in partnership with his father. However, his father declined and disappointed, Danish was left to start over in his native city again. Soon he found a job at Arshad Shahid Abdullah, ASA, a leading architectural design firm in the city, where he found a new home and worked for nearly a decade, leading the Interior Design department. It is also during this time that he married Anis Fatima and had two children, Zenia and Zohaib. After a brief work stint in the Middle East, he finally decided to open his own studio in Karachi, DAZ Design, in 1989.

His private practice, though small in size, thrived for the following two decades with several milestone projects with some of the largest organizations of the country. He worked in multiple domains and continued to add value to multiple retail industries through design. The Opticians trade and Jewelry trade are two noteworthy cases where his contribution was prolific, and his reputation grew to very high regard. He also worked for over a decade for Sheraton Hotels and Regent’s Plaza, contributing to hospitality and lifestyle in the country. He worked in the healthcare, industrial and corporate fields as well. He was also highly sought out for residential interiors, renovation projects; and later, for complete architectural solutions.

In 1992 he was commissioned by a corporate client to design a roundabout in Clifton, Karachi, which they had offered to renovate for the city. Danish’s design became a huge success, making the “Schon Circle” an immediate icon of the city, with great media coverage. The design was a celebration of the basic platonic forms of design – the sphere, cube, pyramid, cylinder and cones, floating over cascading water, elevated over a green belt, touching the edge of the footpath.

With multiple years in the hospitality industry, and especially restaurant design, Danish found the opportunity to design a restaurant for which the brief was to celebrate the culture of Pakistan. “The Pakistani Restaurant” at the Sheraton Hotel, was masterfully done, depicting the varied culture of the country with rustic tree trunks as columns, traditional motifs, details and furniture. The tapestry, paintings and cutlery were all carefully selected and curated as a 5 star experience. This project was much acclaimed and the hotel decided to keep the design despite their policy of decor changes every few years.

In 1996 Danish designed his own home, “DAZ House”, which was nominated for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in the 2001 cycle. The house had several unique features. The ground floor was organized around an expansive open space, centered around a dining space and kitchen, much in the spirit of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie style. The free flowing spaces folded out to a terrace with a swing, and a garden. A pool was nested between the lounging areas,

below a light well. The guest room had a 14 feet long platform, which served as a bed for a large family. The basement had a view to the pool through a window, which was the first of its kind feature in a house in Karachi. The upper floors hosted private spaces with especially designed wind catchers for Karachi’s seabreeze. The rooms also had secret mirror doors which led to a safe room that was also a novel idea. The terrace had a sculpture of a man, who had a secret camera for surveillance in the compound. The triangular form was reminiscent of a ship from outside, with the RCC beams wrapped around a circular column, forming a void where a Chiku tree grew. The house was published in popular press and a TV serial, “Afsoon Khwab” was shot in 1999, directed by Mehreen Jabbar.

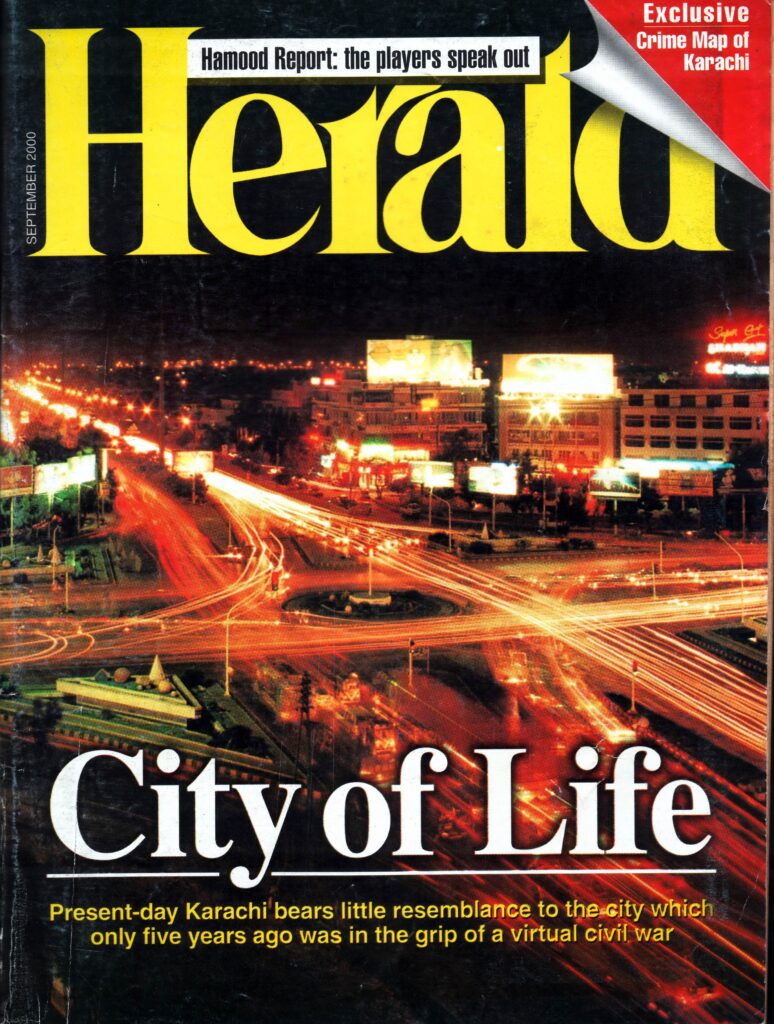

Danish’s work gained great momentum and cast ripples outside the country. He was listed in “Who’s who of Interior Design” and “Who’s who of the world” in the 90s. And his work was featured in “100 Designer’s Favorite Rooms” (1996) and “Great Designer’s of the World” (2000).

Activism and Responsibility

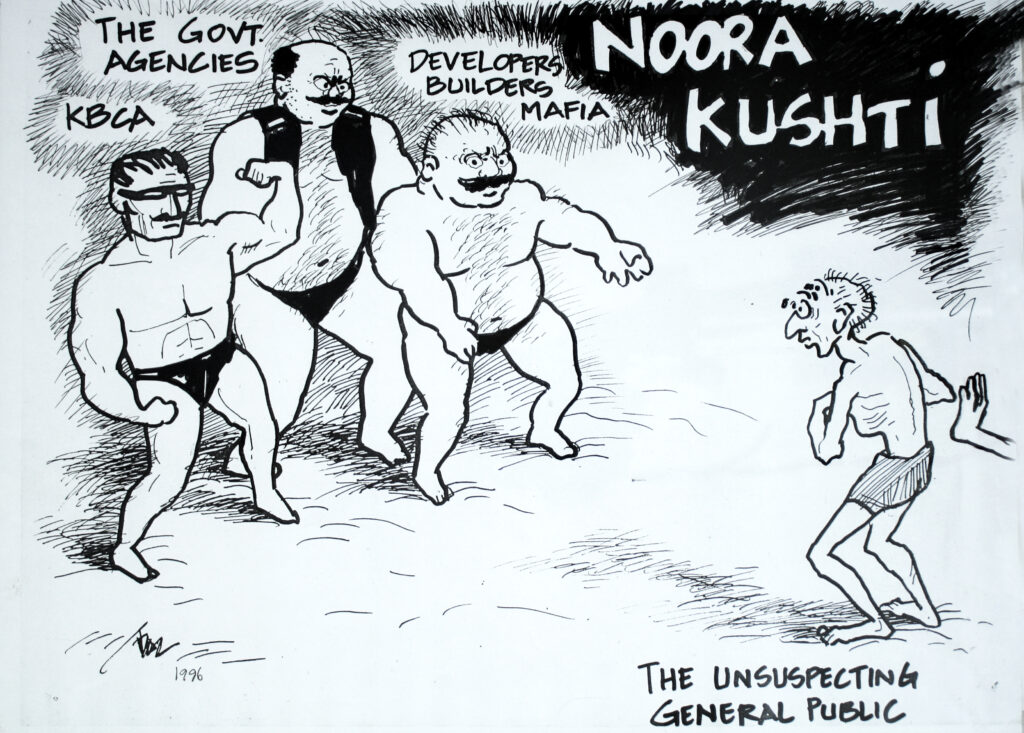

Apart from his design practice Danish remained committed to work for the city, which he saw was hosting a myriad of problems, from aggregating various urban problems to the dearth of public spaces and natural reserves. His motivation led him to connect with other young professional architects and lawyers feeling similarly and in 1988 they collectively founded Shehri, Citizens for a Better Environment, an NGO that continues to work today on civic challenges, land mafia issues, urban environment issues and public spaces.

Danish worked in multiple capacities and projects. He became a regular contributor to the “Letters to the Editor” in Pakistan’s leading newspapers, which featured his opinion pieces, as well as researched work. However, his most celebrated publications were his cartoons and caricatures expressing political satire and commentary. Unfortunately, he started receiving threat calls by the mid 90s and had to stop. It is also during this time that another founder of Shehri was shot, which shocked the organization enough to force the founders to take a backseat.

However, Danish continued to pursue his passion for Urban planning and design, and continued exercises of mapping city routes close to his work and home, documenting various design problems. He also went through an exercise of photography documentation of the colonial heritage in the city, voicing the concern to preserve the old district and safeguard its environment, which was once the most beautiful part of the city. These various exercises of research and documentation led him to his most ambitious work, the “Elevated Grid Cities” project.

He decided to take the gargantuan task of designing the future of the city – how Karachi must grow and offered a fantastical vision of a city on an elevated grid, thriving with urban life; vertically detached from the natural environment. He argued that Mother Earth had already been corrupted by the continuous injection of concrete and tarmac, poisoning its surface; and the abhorrent growth of refuse and waste needs to be processed before touching the earth. Heresearched and wrote on this concept, exploring the significance of “Environments, Products and Systems” (EPS) which he explained are a great framework for analyzing the urban situation. He shed light on the need to intelligently and consciously design these EPS if we intend to coexist decently with the natural order of the earth.

Danish leaves behind a wealth of newspaper clippings, notes, maps, drawings, paintings, letters and other

data in support of this research on urban issues and design propositions. Unfortunately, he was not able to complete and publish his manuscript on Elevated Grid Cities. However, it is evident that Danish worked as a Design Theorist – a rare contribution in the landscape of design and academic disciplines in Pakistan. It is also clear that Danish had demonstrated academic bearings in the disciplines, which would bear fruit in his culture.

Academia and Institution building

Close to the turn of the century Danish started working on two ambitious projects. The first was to create the “Pakistan Institute of Interior Designers” (PIID), which was finally founded in 2000. Much in the spirit of the institute he was a part of in Britain for the betterment of the Interior Design discipline and fraternity; he believed this to be a necessity for the upcoming fraternity of designer’s in Pakistan. He joined hands with several colleagues, including Shahid Abdullah and Naheed Mashooqullah; and delved into its research, by-laws creation and legalities. PIID has since its inception, been a functional national body with some great projects like publications and road shows.

He was also invited by the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture to join their Executive Committee. Here, he was invited by a founder of IVS and long time friend, Arshad Abdullah to

help create an Interior Design Department, with a Bachelor’s qualification. Danish readily accepted and dived into its curriculum research and development. The Indus Valley boasts the first Interior Design Bachelor’s degree in Pakistan, which was authored by Danish and where he served as Head of Department starting 2003.

Personal tragedy

From the beginning of the year 2000 his life took a turn towards tragedy. He lost his mother in 2000 who had remained an important person in his life. In 2001 his father died, whose work he always felt needed to be preserved. However, the most traumatic experience was the untimely death of his daughter, Zenia, in 2003 by a car accident, at the tender age of 20. This left a deep wound in his heart for the rest of his life; which had him secretly struggling with depression for the coming two decades.

For the larger part of his life Danish had remained agnostic, but after this tragedy he gradually drew towards rekindling his faith, which became the most potent force to help him deal with the loss. He spent the following two decades in a disciplined study of the Quran and other religions, leaving behind a substantial unpublished corpus of notes and commentaries on his readings of the sacred texts. He also took out time for painting, as a cathartic practice, a lot of which was also calligraphy. His mainstream practice in design, though continued and gave him the fruits of his arduous labour of the last two decades, did not grow further into a busier office.

Later work

Despite the tragedy and mellowing down of his vigour, in the years to come his accolades continued, with a jewelry store published in Passion Code (2012), an anthology of contemporary retail design projects around the world. His interest in Urban design also found a great opportunity. It was the commissioning of the Edulji Dinshaw Road rehabilitation and design project (2014), through the support of his long time friend and colleague, Shahid Abdullah. His work in the rehabilitation of the beautiful Custom House building, pedestrianizing the road and rendering it with thematic elements of the era; along with a renovation of an ancient Mandor bore great fruit with acclaim and appreciation. For his services in urban design, he became the recipient of the ADA Award in its first cycle in the

category of Public Space Design in 2019. This award from the fraternity of designers with local and international representation was a great milestone, for someone who had started off his career as the first Interior Design professional of the country.

He also continued to work in research, and especially brought forward an idea he had been working on for about a decade, which he termed “Designer’s Social Responsibility” (DSR) – an idea he coined in conjunction with Corporate Social Responsibility. He believed each design practice should offer a ‘design tilth’, a service to the community by means of their design skills. In his personal practice he had continued to do these DSR projects, which were pro-bono exercises and especially in response to some need. He was engaged in multiple small scale projects, like low cost housing, sacred space design and also designed a ‘Straw Bale Housing Concept’ for the Earthquake victims of 2005. However, his largest work was the design of the Ehsanpur Ittehad Model Village for the flood victims of 2011, done with the support of Engro Foundation and Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund. In 2017 at the International Design Conference in Karachi, a joint project of the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture and the Kennesaw University, US; he read a paper titled “Design and Social Responsibility: Ecologically Intelligent Design” in which he formally presented these ideas.

During this period there were three exhibits and events his work was featured in. The first was in 2010, “DAZ Anthology – first forty years” which was a collection of all his multidisciplinary work at the VM Art Gallery. The second was a group show, “Drawing a line” curated by Ayesha Bilal, Rafi Ahmad and Zohaib Zuby, in which the work of four designers was showcased who rely heavily on sketching in their design practice, Danish Azar Zuby, Ejaz Malik, Saifullah Sami, Ali Reza Dossal. The third was in 2022, a three day seminar on Danish’s lifelong work and contribution in the fields of multiple design disciplines, “Fifty DAZzling Years” hosted by the Interior Design department of Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture.

In the latter part of this decade, his undying patriotism and conviction to activism had him rejoin Shehri where he worked on the research and urban planning of

“Gutter Baghicha ” which he saw as the lungs of Karachi, a project which in principle can be compared to the Central Park of New York. He also joined Citizen’s Against Weapons and Anti-VIP Culture agitation groups and societies; where he participated regularly for sit-ins, vigils, and walks. He continued to work as an activist and wrote and drew for the paper until his last years.

Death and Legacy

Danish remained unaffected to the large part by the COVID-19 outbreak, despite suffering from the virus briefly. However, after taking the Pfizer booster vaccine, his health gradually started to deteriorate. He remained ill, suffering from breathlessness, weakness and cough for the most part of 2022; being diagnosed with acute Pulmonary Hypertension. Eventually, he succumbed to Dengue and passed away close to midnight on the 4th of September 2023 at the Tabba Heart Institute in Karachi.

Danish, or DAZ, is remembered as a visionary man with exceptional talent. He possessed unrelenting readiness to work with strict discipline on any task in front of him, and with highest ethical standards. He was a thorough professional, but with a sensitive and gentle soul. He observed a continuous commitment to be of service and remained a patriot his whole life.